August 18, 2017

.avif)

August 18, 2017

.avif)

The last year has been a banner one for fans. Comic Cons across the country drew over 500,000 people to convention centers in Denver, Phoenix, New York, and San Diego. An estimated 1 million baseball enthusiasts crowded the parade route in Chicago, as the long-beleaguered Cubbies celebrated their first World Series win in over 100 years.

And a record-breaking 26 million viewers watched the premiere episode of HBO’s Game of Thrones penultimate season, crashing servers across North and South America. Fandom is undeniably bigger than ever. It begs the question: why? What drives someone to become a fan? What does fandom give us?

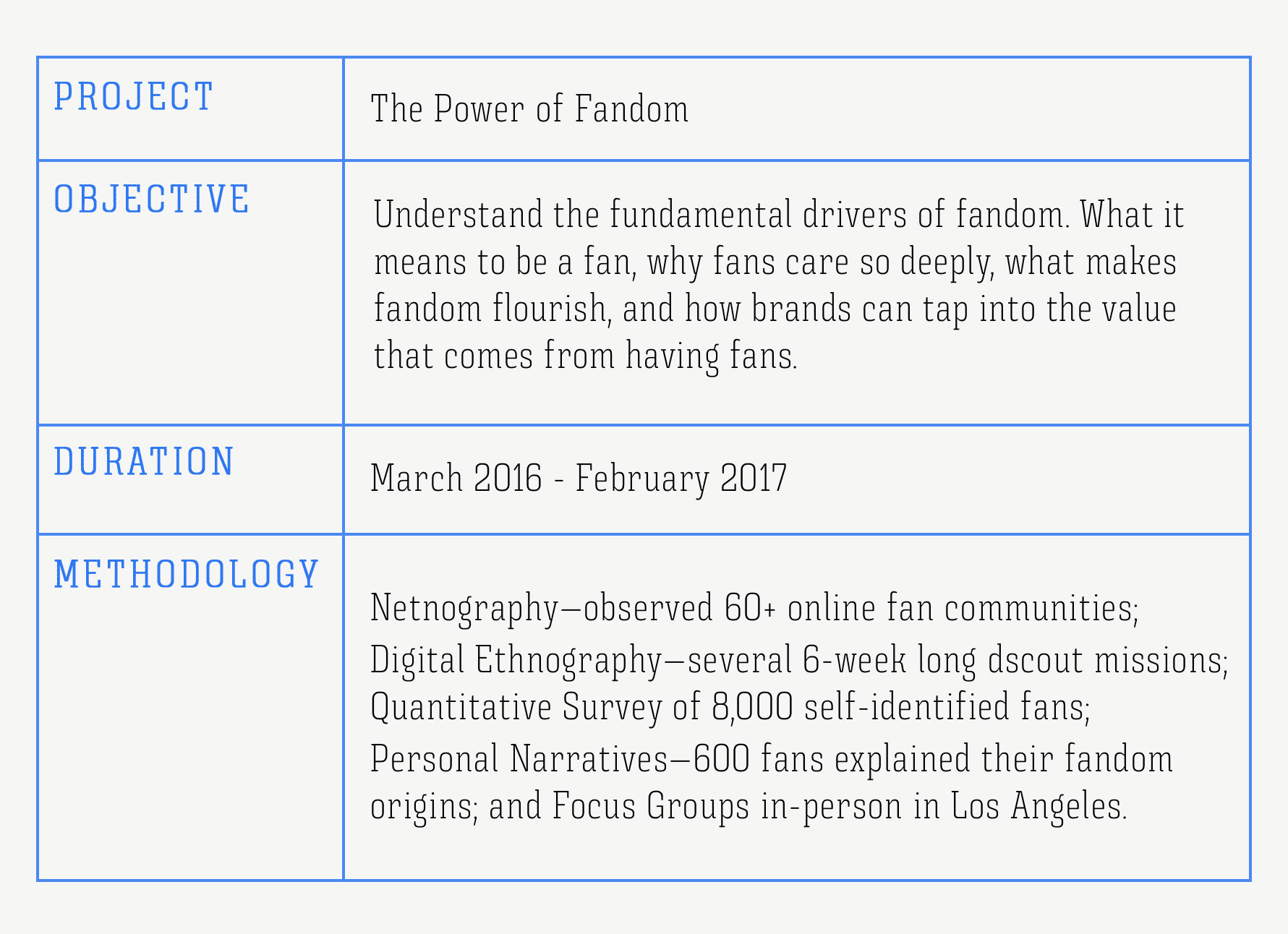

People Nerd Susan Kresnicka is a fan expert, and a fan herself—she claims not a day goes by that she doesn’t watch an episode of Supernatural. From March 2016 through February 2017, Kresnicka led a study on the power of fandom at Troika. (She has since left to start her own firm, Kresnicka Research and Insights.)

The study’s goal was to understand fandom inside and out: to know what it means when we call ourselves fans; to ascertain how fandom is born, reproduced, and potentially fractured; and to learn what bonds and sustains fan communities.

Dscout checked in with Kresnicka, who gave us a behind the scenes look at the methodology employed for the study, the implications for businesses of all kinds, and the conclusions they drew about what makes a fan a fan.

Notes from Susan Kresnicka...

Being a fan helps people understand themselves, take care of themselves, and connect with like-minded others. It's really that simple. It’s a way to better understand who you are, who you want to be, who you have been. And it’s a fantastic way to take care of some of our daily needs, for comfort, for safety, and getting through daily life.

We identified a fairly well nested set of psychosocial needs that fandom fulfills - needs related to identity, self-care, and social connection. We know mechanisms like religion or political ideologies can fulfill similar psychosocial needs. Now, we see that fandom can do it as well.

Identity is multi-dimensional. We have some parts of ourselves that are widely shared with the people around us, and other facets that we feel make us unique and different from other people.

When you see one of the more idiosyncratic facets of yourself in someone else, there's a sense of deep connection. It’s a feeling of “you're deeply like me in this way that feels rare.” The more obscure the thing you're a fan of, the more meaningful your connection is likely to be with that rare other who loves the same obscure thing you do.

We recruited people for the study based on their self-definition as fans. We asked them to consider what it means to be a fan, i.e., to define fandom for themselves, and with that definition in mind, we asked if they considered themselves a fan of something. In our quantitative work, 78% of the 10,250 we initially surveyed said they did consider themselves fans, so most of us think of ourselves that way. (It’s funny, because whenever I give that figure in a presentation, there’s almost always someone in the audience who will say “What’s wrong with that other 22%? How are they surviving?” Because if you're a fan, and you know how much it means to you and how much you get out of it, it’s almost impossible to imagine a way of living where you don't have that kind of relationship in your mind, your life, your heart.)

Obviously a major element of fandom is passion, so the qualitative aspect of the research was hugely important. We talked to a lot of people—we were doing qual in quantitative numbers, for sure. We had close to 3,000 people on Dscout who submitted videos about their fandom.

We didn’t end up selecting all of them for the full six-week digital ethnography exercise, but it was a lot. Over the course of the year, we asked over 600 participants to send us a video whenever there was a moment where fandom proved important, meaningful, or relevant in the course of their daily lives, and to tell us why. That's really all we asked, but that question proved to be the heart and soul of the study.

It would have been impossible to discern how fandom meets core human needs without a tool like Dscout, and watching those everyday moments where fandom matters. We had video after video with people talking about how fandom helps them understand who they are now and who they want to be in the future. How fandom helped them remember the parts of themselves they like best, get through a rough day, or mend a wounded relationship. It was profound.

In the past, fans have been the object of negative stereotypes (and in some pockets still are), but in many ways fandom has become mainstream at this point. To a great extent, the rise of digital platforms has driven this transformation, creating ways for fans of almost anything to find and connect with one another.

For that fan of some idiosyncratic thing, who may have grown up in a small town and could have spent their whole life not having another person to share their fandom with, digital platforms offer a way to find fellow fans anywhere in the world.

Fans can share knowledge, compete, and argue with one another; support and validate each other; and experience a sense of belonging and inclusion. Before the Internet, fans sought one another out, shared fan works, and connected through fanzines that were circulated in the mail. But the Internet offered a next-level solution.

While Silicon Valley may get some of the credit for eroding the stereotype of the “nerdy” fan and for celebrating “geek culture,” I actually think the fact that people stopped feeling so alone, and started being able to find others who felt the same way, helped normalize it for us.

If there’s one thing we learned from this study, it’s that brands that understand who they are, what they stand for in the marketplace, and what they believe in—those are the brands that fans gravitate toward. Identity operates as a filter for the brands you let into your life and the ones you exclude.

There are some brands that do a great job reflecting certain dimensions of who we are, and others we just don’t relate to in any way or even reject as antithetical to who we are. I think we’re about to see a moment where brands talk about identity in a way we've never seen before. You aren't going to get everyone to become a customer.

But if you want the customers you do have to feel totally impassioned and loyal, they have to believe that your brand can represent who they are. That it aligns with them. It’s especially relevant at this current, very polarized moment. People are staking out moral and political identities more purposefully than ever, gravitating towards brands that share their moral perspectives, and rejecting brands that don’t.

I often get asked: “How can we make more people become fans of our brand?” I generally answer: “You can’t.” I don’t believe you can make people become fans any more than you can make two people fall in love. You can hang out in places where you might find a like-minded mate and you can set the mood lighting, but that's about all you can do. Your best bet is to really know who you are as a brand, communicate your identity effectively and authentically, and let the magic happen organically.

As a business, if you've made the decision to pursue a fan-based strategy, then you probably understand the value of a deeply invested, smaller audience or consumer base. It’s about depth, not breadth. But the other thing you have to understand is that you can’t over-commercialize the fan experience. To build long-term relationships, you have to put fans at the center of everything you do, and foster a genuine respect for fans and the value they create within the organization.

You have to think about what you can do to create revenue streams without burdening fans, inundating them, or worst of all, making them feel used. The only reasons we found for people saying “I’m no longer a fan of that,” were perceived moral violations or over-commercialization. Ultimately, the relationship needs to be respectful and reciprocal. Because at its core, fandom is a mutually beneficial relationship between the fan and the brand.

Carrie Neill is a New York based writer, editor, design advocate, bookworm, travel fiend, dessert enthusiast, and a fan of People Nerds everywhere.