Topics

April 7, 2022

.avif)

April 7, 2022

.avif)

Last quarter, Dscout and User Research Academy partnered together to run a study. We were interested in exploring generative research methods and wanted to use remote tools to explore an abstract ideological topic and educate ourselves in the process.

We decided to run a study on body positivity and Health at Every Size (HAES). Surveying 26 scouts who self-reported some form of experience, activism, and/or community leadership in one or both of these topics.

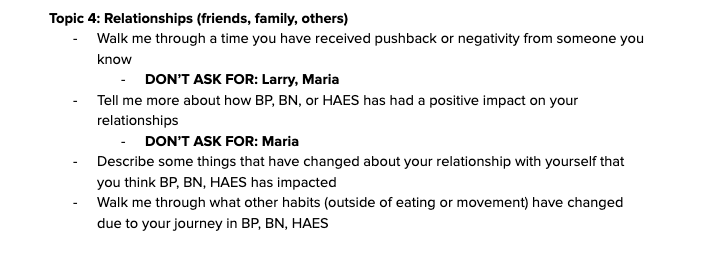

The project consisted of a six-part Diary mission on Dscout, followed by a series of 1:1 interviews on Dscout Live. We learned all about our scouts’ relationships with body positivity or HAES, how they got to where they are today, and how their relationships with their bodies have changed over time.

A top concern for us while we ran this study: body image is hard. Many of us have complicated and sometimes very painful emotions about our bodies. We wanted to find a way to find out more about people’s relationships with this topic while still respecting our participants’ boundaries.

Please note that while I don’t claim to be an expert on this subject, I do want to share a set of actions and ideas we tried in the course of running this sensitive project. Consider incorporating some of these ideas in your future projects to help participants feel more comfortable and respected while participating in your studies.

The first consideration is very high-level. When scoping a sensitive topic, it’s important to factor in the vulnerability and potential harm or pain your participants might experience while participating, in addition to the more standard considerations of cost, sample size, demographics, resourcing, and the like.

We recommend asking yourself questions like:

As a researcher, my first inclination is always to go directly for collecting data in the moment from people who are living a situation. But if the experience you’re looking to learn more about is potentially painful or even traumatic, it’s worth pausing and asking if you really need that immediate experience, or if you can instead talk to people who are a little further removed from the situation.

As a research team, our first inclination was to study body image—how people today feel about their bodies, and what insecurities they’re currently struggling with. This was an interesting thought, but we also considered the following:

Ultimately, we decided that what we would gain from such a study wouldn’t be worth the potential harm. Fortunately, we have a lot of flexibility in what to study and decided to pivot our scope.

Instead of studying body insecurities, we focused on movements celebrating healthier relationships to bodies, such as body positivity, body neutrality, and HAES.

Instead of a broad recruit, we decided to focus on a specific subset of people who identified strongly with body positivity and/or HAES. We figured that these folks already have this topic on their mind and will have thought a lot about their own relationship with their bodies.

We also designed the study to focus on the movement of body positivity and HAES and decenter questions that had to more directly do with people’s negative experiences with their bodies.

When it comes to some sensitive topics, you don’t always know what you don’t know. This is especially true if you intend to research communities or experiences that you don’t have a personal history with.

Before pen goes to paper on research design, take some time to do secondary research and try and get a basic understanding of the space you’re about to research in.

In particular, keep an eye out for terminology to use and avoid while phrasing your questions, and keep an eye out for questions that might be harmful to ask. You may also want to find out whether there are experiences common enough that they would be worth diving deeper into during your research design.

Outside of secondary research, you could also consider asking around internally to see if anyone in your organization’s network is already an expert in the topic at hand and might be able to provide you with some expertise while drafting your work. “Experts” don’t have to be researchers—they could be advocates, community leaders, or someone else who has dedicated thought work to the topic at hand and is accustomed to speaking about it.

NOTE: Remember, Do NOT associate an “expert” with “someone who shares traits with the target community.” They are not one and the same. It’s unfair to expect one person who has no other training to speak on behalf of an entire community!

While considering our screener, we sent messages out to the Dscout community to see if we had pre-existing connections to professionals in the body positivity and HAES communities.

Through co-worker connections, we found three professionals in the health and fitness space who work through HAES. We asked them these questions:

The answers we received became a foundation that ultimately helped us design our screener and better phrase our questions in the study itself.

It’s unfair to ask participants to give up vulnerable information for unknown reasons. Communicate to people what their information will be used for and who it will be shared with. Do this in the screening phase so they know what they’re signing up for (and why) and reiterate it in the research process.

Doing this has two benefits. The first is that it will make participants feel safer telling you sensitive things if you tell them where and how their information will be used and assure them it won’t be shared outside of those contexts.

Secondly, it can be empowering to let people know how sharing this information might be worth something to them by improving their own lives or the lives of others. (If your study isn’t doing that, should you be running the research? See point one.)

It was important to us that our scouts understand that their answers may be included in a public-facing blog. We included the following copy in our screening process:

The mission you’re applying for is all about sharing your experiences, wisdom, and resources when it comes to body positivity, body neutrality, and/or HAES.

If accepted, the answers you provide in this study may be used in a public-facing capacity, in classes, or on Dscout's public blog. We would not reveal any personal information about you, and no sensitive responses will be shared without additional consent. Are you comfortable with these terms?

We also included the following copy in the description of the project:

Hi there! We're excited to invite you to our study on Body Positivity, Body Neutrality, and Health at Every Size. We are so excited to learn more from you about your experiences and philosophies around this important topic.

IMPORTANT NOTE: This study is being conducted in part by the marketing team at Dscout. If you choose to participate, some of your answers may be published on our blog, People Nerds In addition, your answers may be used as examples in classes on research methodology.

If you feel comfortable about your story being shared on these platforms, then please accept this mission and get started! However, if you are not comfortable with this, we totally understand—feel free to decline the mission, and we hope to see you in other opportunities down the road.

If you have more questions before beginning, you can accept the mission and use the app to message us questions. You can always opt out later if you want.

If you do decide to participate, welcome ? Please complete the first part by October 17 at 11 PM CST to confirm your spot in the study. We're looking forward to learning from you!

It also ended up being very personally impactful for our research teams to read many of the stories that were shared with us. We sent personal messages to each of our participants at the end of the study, personally thanking them for what they decided to share and letting them know the impact it had on us.

When running research on sensitive topics (or honestly on any topic), it’s important to consider what questions should be considered optional and how that is going to be communicated for the study.

In my opinion, if the topic has the opportunity to cause a lot of harm, every question should be optional. This gives participants the maximum amount of agency and trust in a situation where they are providing large amounts of trust by sharing vulnerable information about their lives.

In order for something to truly feel optional, the message needs to be communicated multiple times. Surveys, by design, are using something that feels an awful lot like a ‘test’—the implication of a survey is that all questions are mandatory. Shifting participants to a place of more agency means giving opt-out options in multiple places—in the survey description, at checkpoints, and even in the copy of particularly difficult questions.

We ended up communicating the option to opt-out in our project by using a code word that people were always welcome to give instead of answering. Using a clearly communicated code word takes the onus off of participants to say something more direct like “I don’t want to answer this question” or “I don’t feel comfortable,” which might feel intimidating to write.

Our code word was “pineapple.” It was a little silly, but we hope that this made the opt-out option feel low-stakes to take.

We included the following copy in every part description:

Please note that most questions in this part are optional. Keep in mind that answers you give may be published anonymously on our public blog. If you ever feel uncomfortable answering a particular question, you don't have to! If you wish not to answer, just say so.

Or, just use the code-word pineapple? in place of an answer.

People took advantage of this using some of the following responses:

This technique appeared to be successful enough that some participants even carried the language over to Live interviews, as can be seen in the following excerpt:

Interviewer: I’m curious, how did you move from body positivity to body neutrality?

Participant: So like, I remember in high school—there are some pineapple aspects of this, but…

Overall this seemed like a successful way to give people a consistent and memorable way to let participants opt out of questions without having to say anything directly.

If you are running follow-up studies in multiple stages, then opting out can provide an additional level of information. Take time to review who opted out of which questions in your study, and consider what that might mean for additional stages

For example, if one participant consistently opted out of a certain subject, then you can choose to not even ask them about a particular issue in future stages (or communicate even more clearly that they can skip that part of the research).

If several different participants opted out of a single question or part, that can be a clue that this subject needs a different approach—or just needs to be left alone with this particular sample.

Our study consisted of a diary study with follow-up Live 1:1 interviews. After we drafted our interview guide, we reviewed our survey responses from our follow-up participants. If someone opted out of a diary question, we made note to not bring it up in our 1:1 interview unless they brought it up first.

When it comes to sensitive topics, it’s hard to know how much emotional energy participants will be spending responding to your questions. With that in mind, consider breaking your surveys into smaller pieces than you would normally.

Note: If you’re using Dscout Diary, this would mean a lot of parts with a small number of questions, rather than one part with more questions.

This technique gives people the option to more easily take breaks without having to feel like they’re stopping in the middle of something.

Additionally, some topics are more likely to be hard to talk about than others. Breaking your study granularly by topic gives you the opportunity to give people a warning that a particularly hard topic is coming up, so they can put down the study and come back when they’re in a better headspace to talk about it.

We ended up fielding a six part survey using Dscout’s Diary tool. No part had more than six questions at a time. This gave people a lot of space in between entries to take pauses.

We also included extra warnings around the parts of our study containing information that our exploratory interviews deemed as potentially painful (e.g. people’s relationships to diet and exercise and people’s relationships to others in their lives).

Another extra accommodation you can give participants talking about sensitive topics is more time. Participants may need extra flexibility to find the time, emotional bandwidth, and / or private space to think about and answer your questions. Consider extending your timelines to give people a few extra days to answer your questions well.

If you are working in Dscout, you can also consider making your mission automatic. This will let people move through parts at their own pace, providing an additional level of flexibility to their participation.

Although the study was relatively short, we gave people a full two weeks to fill it out to ensure that people had the time and space they needed to think through the prompts.

We also elected to make our mission automatic, and only gave intermittent reminders so people wouldn’t feel too badgered or rushed.

These tips have all been on how to field sensitive research—how to interact with your participants to minimize emotional burden while learning about difficult topics. But it’s important to keep in mind that our responsibility to our participants, and the emotional information they shared with us, doesn’t end when we stop interacting with them directly.

As researchers, we are often looking for emotionally impactful stories to tell. But it’s important for us to pause and think hard about how we do that, especially if the emotion we’re sharing is pain. If you’re running research on a sensitive or painful topic, it’s worth thinking about how to communicate your story without centering or fetishizing the pain that people trusted you with. How can we show the negative impact our research topic has on our participants’ lives without putting their deep wounds in front of strangers unnecessarily?

What this looks like in practice will probably vary from deliverable to deliverable. After all, the question of how to analyze and present sensitive information is a difficult and nuanced one. But I think it’s important to keep in mind nonetheless since you’ve spent valuable time and effort building trust with your participants and helping them to feel safe sharing sensitive information. As researchers, it’s up to us to uphold that trust, long after the project has left the field.

Karen has a master’s degree in linguistics and loves learning about how people communicate with each other. Her specialty is in gender representation in children’s media, and she’ll talk your ear off about Disney Princesses if given half the chance.