Topics

April 1, 2021

.avif)

April 1, 2021

.avif)

"I love it when the people I'm working with make me feel valued as a person...that my opinions really matter to their work. They want me to take this seriously and they're committed to sourcing honesty about their products."

Adrienne, 43, CO

"I want to feel like I'm adding value to what you [researcher] are trying to accomplish, but I also want to have fun while I'm doing it. I'd like it to not be boring. I want to see and hear the personality of the person interviewing me."

Alana, 30, GA

"I really like it when researchers encourage you to express yourself creatively. Drawing something, showing something, thinking outside of the box about what you want me to do, all of those things help innovate and keep me interested in the project."

Anonymous, 32, CA

Nearly everything in our world was impacted and affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For us in user experience, the “new state of things” invited us to think differently about our interactions with participants.

Operationally, the way we “keep the trains running,” has changed—with many of us relying more heavily on remote approaches. Ethically, we were offered moment for reflection about the nature and meaning of "doing" research:

For some, these and other questions led to a pause in user research. Safety concerns (e.g., asking participants to visit retail locations could endanger health) merged with moral questions about the need for, uses of, and people comprising user research. Insights professionals began to reevaluate the impact of their work.

For example: recruitment practices like partners, communities, and the instruments used to qualify and disqualify a person; participant "management" and how those processes and behaviors might be extractive or transactional, instead of cooperative and community-building; when are participants incentivized, by what methods, and what are the amounts?

Against that backdrop comes this brief report, which seeks to showcase how research performed by the UXR community is perceived by those who make it possible: the humans who volunteer to join panels, download apps, sit for focus groups, and take platform surveys.

What makes a research study design and its commensurate activities valuable to participants? What best practices can be gleaned from investigating the investigated?

The diversity of experiences and subject positionalities represented here do not constitute the universe and breadth of research "participant," but does begin to offer a window into the motivations for and perceptions of the work so often conducted to champion and foreground the "human" in "human-centered practices."

The data were collected over 24 hours via a media-forward survey tool called Dscout Express. Over 250 folks completed 10 questions (open-ended, closed-ended, video, and scale) about their experiences with, perceptions of, and suggestions for user research via their smartphones (although the work was fielded on Dscout, participants were encouraged to reflect on their experience with all forms of research, both in-person and digitally).

The only inclusion criterion was that folks reported taking part in research studies longer than "a few weeks," which was introduced to surface views from folks who had multiple experiences in and with studies. For a fuller sample characterics readout (including some demographics), please consult the Appendix.

The primary focus of this research was to foreground and untangle the characteristics and features of a "valuable" research study from the vantage point of the participants who make them possible. Open-ended and media question types were leveraged to offer folks the most flexibility in describing their experiences. To begin, participants were asked to offer a percentage value of those studies they rated as "valuable," from 0 to 100.

The average percentage of studies this sample deemed valuable hovered around 70 (69.38%), with 23 participants giving a rating of "100" and four offering a rating of less than five. The most-reported percentage was "75," indicating that, on the whole, these participants found studies valuable, broadly defined.

This trend did not seem to change when filtered by primary motivation for participating in research; that is, value did not change when participation was primarily for remuneration vs. sharing opinions vs. improving products.

When asked to define "value" in three words, many participants homed in on a few themes that would again surface in their more detailed video responses:

This might include learning about a new product, having the chance to improve an existing one, or having the opportunity to share a frustrating (or delightful) experience weighing on one's mind.

"I really enjoy being able to participate and contribute, especially since I'm living alone—I like the connection and feel my opinion is valuable...it's meaningful to me."

Randi, 56, CA

Many folks described frustrations over clunky question wording, inconsistent messaging around project expectations, or unanswerable questions (I'm not sure what you're asking!).

"One of the things that's frustrating is when I'm not able to mark responses that accurately reflect myself or my experience. Be careful with survey or screener questions."

RK, 36, GA

"Be clear in your question-framing. In studies I'm often asking myself 'What are you even trying to get out of this?' and it gives me anxiety because I'm trying to do a good job for you."

Justin, 28, NV

This sample showed detailed and nuanced criteria for evaluating the ROI of participation. This usually meant knowing the set of activities or questions ahead of time and if changes are expected.

“You've got to pay a reasonable amount for my time because otherwise I don't have fun and I don’t feel like I'm valued at all."

Lisa, 35, MI

Underlying many participants' responses was a sense that valuable studies were those that considered the human on "the other end" and the effects research has on them. Is the work an effort to understand or just know?

"Some work feels like free advertising for your product or service. Are you trying to capture real feedback or just get some free advertising for a new feature?"

Anonymous, 33, WA

"Have a plan and be prepared. Know what you want to test or want feedback on before going into it. It doesn't feel like a worthwhile session if I feel the questions weren't thought out."

Stephen, 35, KY

A summary view of participants' adjectives reveals a higher-level look at these (and other) trends. Words and phrases related to time, rewards, and considerations related to the study or research designs were frequently mentioned. If insights professionals learn one thing from this work, it's that today's participant is savvy and attuned to the nuances of "good" design.

Analysis of video responses added detail and complexity to the definitions of value for participants. In addition to the themes outlined above, these folks described craving more human connection during interviews, preferring time to engage with a product or service before reviewing it, and challenged researchers to bring more creativity (and systematicity) to their designs.

Time-and-time, these participants mentioned confusing question wording, nonresponsive researchers, or formats that didn't match the feedback solicited (e.g., scale not allowing for nuance compared to an open-end). It was striking the amount of responses mentioned how researchers' designs hindered "doing a good job" from the participants' perspectives; these folks want to offer feedback and data that is useful, but felt that the activities offered could stand in the way of that.

Before exploring perceptions of and activities leading to value in research, folks were asked about their baseline experience with kinds of research, their reported time participating, and the broad rationales for starting. Dscout’s panel is nationally-representative, and although the sample size isn't large enough for conclusive inferential statistics, it does offer a slice into the current state of experience, product, brand, and market research being conducted today.

Participants were equally distributed across temporal categories of research participation, with nearly a third (32.5%) reporting three or more years of experience. When asked about "a typical" week (an arguably confusing term these days) of research participation, these folks indicated an average of three studies, with most participants reporting involvement in just one.

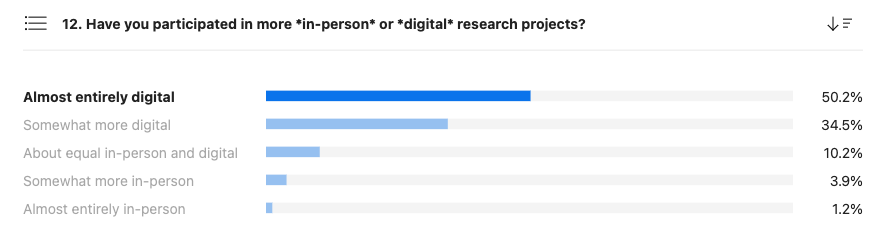

Again, question framing strived for all kinds and types of research, not just those undertaken on the Dscout platform, but including in-person work as well. When asked, however, about their experience with research modality (e.g., in-person vs. digital), responses were skewed toward digital, with the fewest responses being "almost entirely in-person").

When asked to select their top two reasons for participating in research, most reported remuneration, either in the form of direct payments or gift/credit.

Three reasons were closely reported second, "Improve products/services," "Learn about new products/services," and "Share my opinion generally." Each had just over 30% frequency.

"Other" reasons included a general interest in data and how research worked and framing research participation as a "better" habit for passing the time. The influx in job insecurity and unexpected unemployment in 2020 and early 2021 might explain the skew of these results. It is worth reiterating the importance of non-monetary motivations for this sample. Specifically, research participation as another way to connect with and impact the brands folks engage with and purchase from.

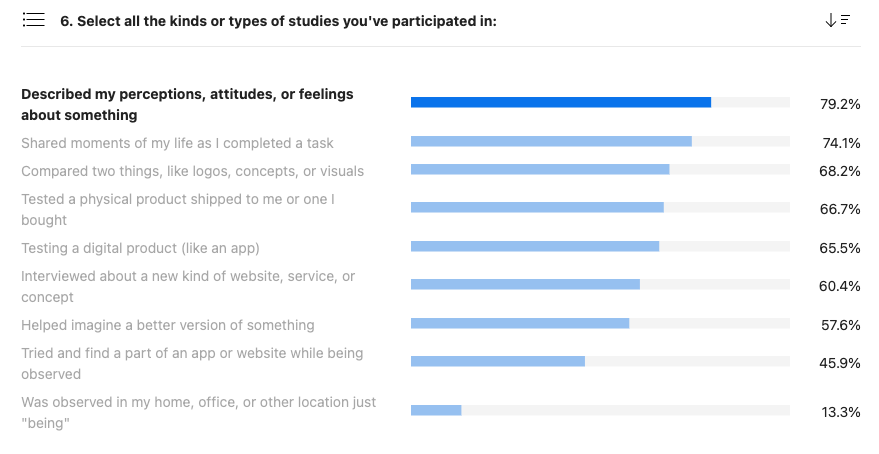

Finally, participants responded to their experience with various kinds of research designs. The options were derived from interviews with internal researchers at Dscout and a content analysis of work launched using the Dscout platform.

Like with the modality responses, here too is a pattern for more remote or digital designs compared to in-person, indicating a potential recency effect. Interestingly, most designs were recognized by participants, showing the rise in popularity (and diversity of application) of remote experience research. Increasingly, insights professionals are turning to digital platforms for more than "just" usability work and leveraging these tools for co-creation, concept tests, product unboxing, and even ethnographic work.

Several currents feed and drive the increased demand—and need—for user research: a competitive marketplace, savvy, socially-connected customers who can evangelize or detract with the tap of a keyboard, and the shrinking attention window into which experiences must captivate and serve.

As more business units get involved with insights gathering (democratization) and as the questions grow from tactical (which do you like?) to strategic (which way should we go?) researchers owe it to the folks—the humans—who make such decisions possible with their time and data.

As this brief report demonstrates, research participants are hungry to help, earnest to do a "good job," are acutely aware of the time such work takes and the impact their responses can have on a business's goals.

In order to truly "do" human-centered research and build products that "excite, "delight," and "create fans," we must consider the whole-human, the people on the other side of the surveys, the tests, and the interview screens who power the entire enterprise. Creating valuable research for our participants also means creating a more cooperative, mutually-beneficial ecosystem. Experiences only stand to benefit by prioritizing the "human" in their human-centered insights practices.

Participants ranged in age from 24 to 74, with the majority (41%) between the ages of 25-34. The sample skewed folks who identified as "woman" (53%) and "white" (51%). Most participants were college graduates (44%) currently employed full-time (68%). Household composition was mostly "with partner/spouse + child" (42.7%) and reported income between $25k and $100k.

Ben has a doctorate in communication studies from Arizona State University, studying “nonverbal courtship signals”, a.k.a. flirting. No, he doesn’t have dating advice for you.