Topics

December 1, 2021

.avif)

December 1, 2021

.avif)

This report is part of a series on how project timelines impact the modern user research practice. Download a full report, and accompanying assessment of your team's time-buying strategies, here.

Or read the other articles: Left Behind: 300+ UXRs on What Makes for an Adequate Research Project Timelines and Buying Time: A 6-Approach Framework For User Researchers.

To the extent that an organization’s efficiency depends on the interconnectedness of its business units, teams, and front-line practitioners, any small disruption in workflows has the potential to ripple upward, affecting long-term strategy and OKRs.

People Nerds’ recent examination of the role and impact of time in user-centered insights professionals’ work has largely focused on the micro-level: the tactical, personcentric outcomes: What are the average completion times for projects and how do UXRs advocate or create the space for more time?

These findings paint an important, but incomplete picture. Thus, in our final chapter, we’ll fill in that picture by unpacking the implications for those building teams, growing companies, and working with insights functions.

One of the most important and repeatedly-examined concepts within the humancentered community is “alignment.” We optimize for alignment within teams (e.g., how aligned are two UXRs on the best approach for supporting stakeholder asks) and between teams (e.g., how aligned are stakeholders with their insight-delivering partners).

Intra- and inter-team differences can take many forms, but expectations around project, insight, and outcome delivery is certainly one realm of misalignment that pervades the user research space. In short, UXRs and their stakeholders aren't always aligned on how long it takes (or ought to take) to complete any research request.

When 300 user experience professionals were recently surveyed about their perceptions of project timelines, they were asked about the extent to which they were aligned with their stakeholders.

Almost half (49.2%) of participants reported being "Somewhat aligned" with their stakeholders, while about a third (34.4%) reported being "Mostly aligned". Fully 10% of participants reported they were "Not at all aligned" and only 6% of respondents felt they were "Aligned perfectly" with their stakeholders.

Not great news, but not entirely terrible news either. For this sample of UXRs and leaders, a significant minority reported good alignment, and the lion’s share of folks reported at least some alignment on the time expectations to complete research projects. As we reported elsewhere, misalignment—usually with stakeholders expecting faster turnaround times than UXRs—can have organizational implications. Specifically:

In addition to asking about perceived alignment, participants reported their current or most-recent team structure, electing one of the following response options (followed by the proportion of that structure in our sample):

We crossed these team structures with variables examining stakeholder alignment, median days to complete a recent project, and the elements of executing research that typically elongates timelines. This created a unique profile for each org structure.

The team structure with the least amount of reported stakeholder alignment was “Hybrid,” which was the only one with a double-digit percentage of “Not at all aligned” (nearly 16%).

“Embedded Across Teams” is also of note here, as it had the smallest percentage of “Mostly aligned” reports (21.3%). Both freelancer and solo reported more “Mostly” alignment, at 57.9% and 43.8% respectively.

For this sample, it seems that structures which disperse UXRs across an organization (hybrid and embedded across teams) are less aligned than structures with smaller teams or teams-of-one. No team structure had a majority of UXRs reporting being “mostly” aligned with their stakeholders; whatever team structure, leaders might consider prioritizing alignment-increasing activities.

Recruitment, site issues, and other operations issues was the most reported reason for time delays for every single team structure, paralleling the results we surfaced in our top-line readout.

Operations—especially the management and support of recruitment—comprised no less than a quarter of the reasons for project timeline elongation and was as high as 47.9% (for solo researchers). These data, as well as research with organizational leaders, continues to spotlight the importance of operations professionals. When UXRs have support professionals to organize sites, manage recruitment, and establish partnerships for incentives, there is more space (and time) for collaboration and—ostensibly— stakeholder alignment.

After issues with research operations, participants across team structures mentioned “assets for research” (e.g., awaiting prototypes, app versions or other elements necessary for their work), “approvals/IP/legal matters” (e.g., uncertainty around what they can legally ask and show would-be participants), and “scope creep” as features elongating their project timelines. The first two could be slotted under the broader operations umbrella, while the third is another sign of misalignment between stakeholders, collaborators, and insights professionals. As we uncovered in another report, many of these participants leverage educational and advocacy-like strategies to “buy” more time for their work.

Time-buying strategies (our open-ended analysis produced six in total) were crossed with both the median days to complete a project and team structure, producing teams-based profiles.

To quickly recap:

First, we examined how the strategies folks’ reported might relate to the typical length of a recent project. Results showed that professionals working on shorter projects relied most on the strategies of “White-Knuckling” (e.g., working weekends) and finding “Efficiencies” (e.g., running research activities simultaneously).

Those working on longer projects relied most on “Tricks-of-the-Trade” and “Educate/ Advocate” to minimize time pressures. It’s important to note that “White-Knuckling” was reported as a strategy only by eight participants in our sample.

Here is a full breakdown of the strategies for obtaining more time and the median days to complete a research project:

We can’t tell from these data, what the so-called “direction of causality” is. It may be, for instance, that White-Knuckling shortens timelines, such as when UXR pros work extreme hours to wrap projects. Alternatively, White-Knuckling may only be a viable time-buying tactic for shorter projects, with longer stints of the grin-and-bare-it approach risking burnout.

We also aren’t able to tell from these data if longer timelines necessarily meant better, more rigorous projects (or if shorter timelines adversely impacted output quality). We do have evidence from these data that UXRs believe more time produces more impactful, rigorous, and creative research.

Second, we were interested in how a UXR’s team structure related to their reported strategy for securing more time to complete a project. As previously reported, the most frequent time-buying strategy involved educating stakeholders, collaborators, and clients on the rationale for research design choices.

Drilling down further, we uncovered some team-specific differences of note:

In general, these data suggest that for most UXRs, attempting to advocate and educate stakeholders is the go-to method for buying project time, after which their team structure plays a role in determining their secondary strategy.

Here is the complete breakdown of time-obtaining strategies crossed by team structure:

Finally, we examined whether those time advocacy strategies that are more communicatively engaged associate with greater stakeholder alignment than those that are lower in engagement.

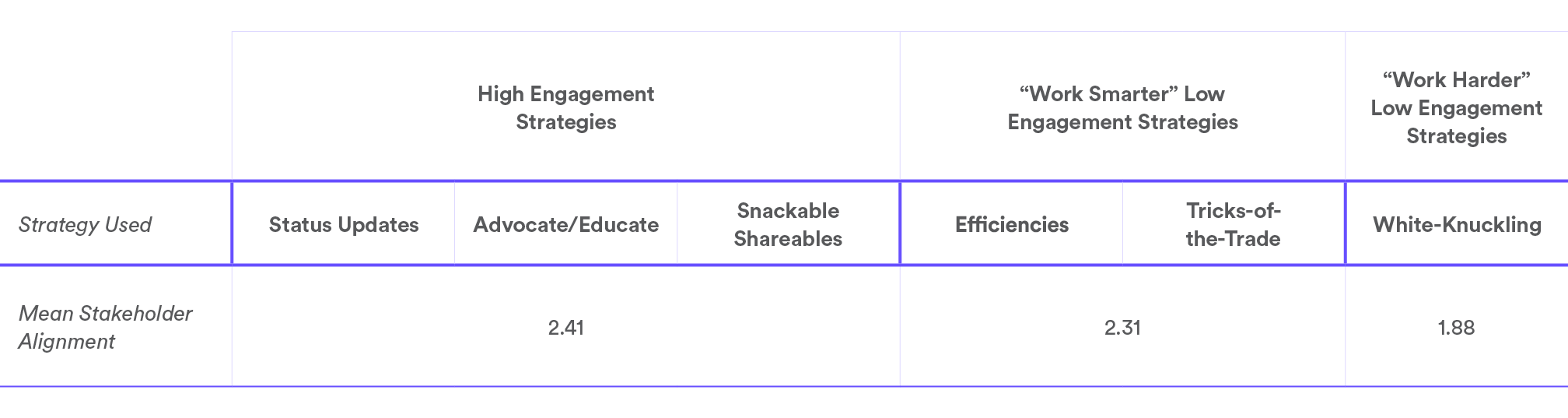

To do this, we grouped the time advocacy strategies into supra categories, based on their level of engagement. The first supra category reflects the three high-engagement strategies (i.e., Updates, Advocate/Educate, Snackable Shareables). The second supra category reflects two low-engagement strategies that reflect a “working smarter” approach; these folks don’t appear to engage stakeholders directly to buy more time, but use efficiencies or using tricks of the trade to resolve (or preempt) time crunches.

The third and final supra category consists solely of the White-Knucklers—those simply “working harder” and “putting their heads down” to meet deadlines.

High engagement strategies report highest stakeholder alignment (mean = 2.41), followed closely by “work smarter” low-engagement strategies (mean = 2.31). The least stakeholder alignment was reported among those (admittedly few respondents) who reported the “work harder” low-engagement strategy (mean =1.88).

What might these data mean to a leader interested in the twin goals of on-time insight delivery and creating processes/workflows that enable their user insights professionals?

The first is to advocate for your team in stakeholder and cross-team meetings, and to coach UXRs to do the same. This was a strategy most-reported by our sample and one that “allowed for” longer project completion timelines.

User experience research—although a burgeoning field—is still evolving and maturing. It is critical to remind the organization of its role in advocating for the customer and creating the space for good design.

Admittedly, this may frustrate front-line practitioners, who feel that advocating for their work feels precarious (as designers might have 20 years ago). These data seem to suggest, however, that it may “pay off” in added time, which can help UXRs execute to their full potential and delight stakeholders, to the benefit of users and customers.

The second is to consider one’s team structure. This might be out of a leader’s immediate control (e.g., budgets, internal organizational maps, growth curves), but these data suggest it does have an impact on important business-wide outcomes, such as cross-team alignment, project delivery timelines, and project quality.

Specifically, team structures where UXRs work more closely together—either in a single unit such as an agency or embedded together within a team—produces more collaborative time strategies such as advocacy and updates and reported shorter completion timelines. When UXRs are organizationally dispersed—embedded across teams or within a hybrid structure—perceived alignment drops and time to complete projects ticks upward.

Ben Wiedmaier is a content researcher/producer at Dscout where he spreads the “good news” of contextual research, helps customers understand how to get the most from Dscout, and impersonates everyone in the office. He has a doctorate in communication studies from Arizona State University, studying “nonverbal courtship signals”, a.k.a. flirting. No, he doesn’t have dating advice for you.

Kendra Knight is an associate professor of communication studies. She completed her MA and PhD in human communication at Arizona State University. She specializes in work/life communication, “casual” sexual relationships and experiences (e.g., friends with benefits), and interpersonal conflict and transgressions.